Report from the indigenous community Puente Quemado 2, which demands the return of territories and the withdrawal of the multinational Arauco. “The monoculture of pine trees is a tragedy and we are going to fight to recover the forest”, says the Mbya cacique. In the 21st century, they have no water or electricity. The complicity of the government, the violation of rights and extractivism.

The building is made of wood, about ten metres long and seven metres wide. It is white and light blue in colour and already worn out. It is the school of the Mbya Guaraní Puente Quemado 2 community, 150 kilometres from the capital of Misiones. A sheet metal roof, a very small green blackboard and half a dozen tables. All very humble. And, in the 21st century, it has no drinking water or electricity, but they do say there is a tall, neat flagpole for the flags of Argentina and Misiones to fly. Like a bad joke of power: the national emblem is not missing in spite of the sea of needs and violation of rights.

It is Friday morning. Five days of rain are behind us. The sun is out and it is “cold” for the climate in Misiones, about 15 degrees. The starting point is Aristóbulo del Valle. The van zigzags while dodging puddles of water and a variety of wells that can be misleading. Vasco” Baigorri, a communicator with the Aboriginal Pastoral Missions Team (Emipa) and with a long history with indigenous communities, puts his foot on the accelerator, perhaps going faster than is convenient, but he has in his favour the fact that he knows the missionary roads.

As they walk, they can see the native bush, farms and, with impact, the monoculture tree plantations of the forestry companies. They look like an army: green, neat and in a row. The silence of the green desert is also surprising: no birds can be heard in these trees, a reflection of the monoculture and the lack of biodiversity and almost absence of life.

The vehicle advances along the dirty road – the provincial route 220 – and, kilometres ahead, the native jungle appears, the variety of greens in trees, bushes and palm trees that never cease to surprise. And everything contrasts even more with the red earth and the unpolluted blue sky. Until, at a sudden crossroads, I turn right and see dozens of hectares razed to the ground, trees cut to the ground and barren land, as if a nuclear bomb had spilled out. There was no explosion: it was the “harvesting” of trees destined for sawmills and pulp mills. The forestry machines razed everything to the ground. Only the pindó, a type of palm tree, is left standing. Cintia Gimenez, from Emipa, explains that the popular saying warns that if a pindó is cut down, the man will lose his virility.

Photo Emipa

The landscape will repeat itself for an hour. At times there is native bush. For many other kilometres there are pine monocultures.

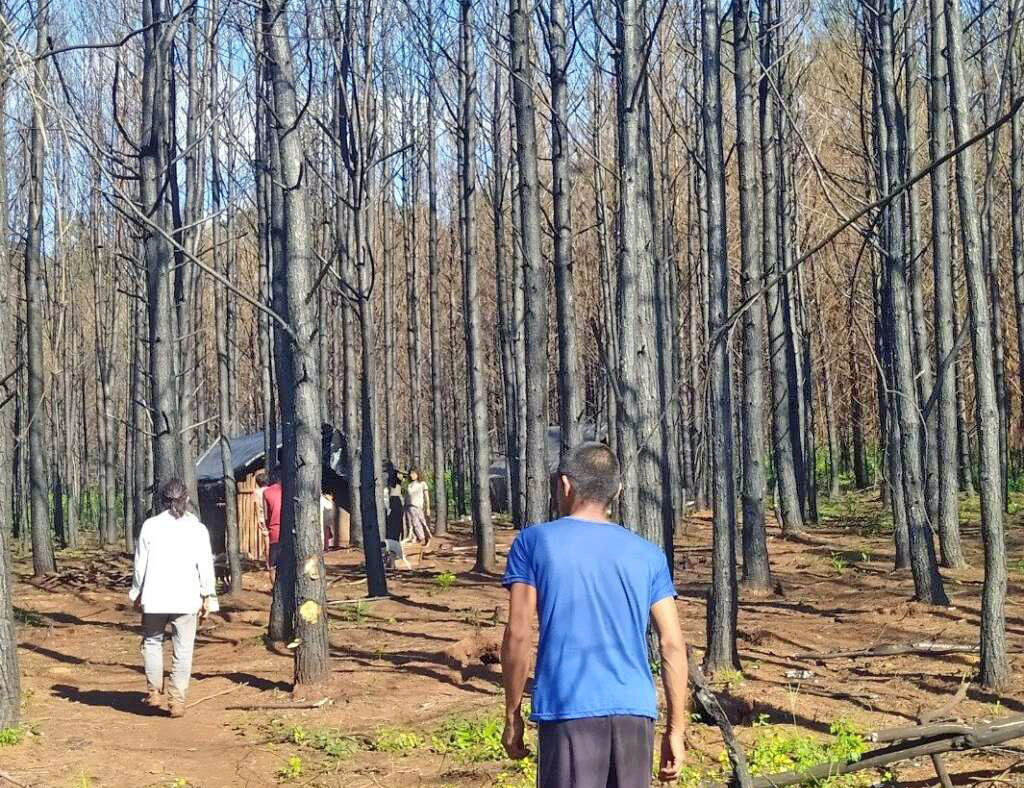

After more than an hour’s walk, a graveyard of burnt pine trees, still standing, comes as a surprise. They are the anteroom to the Mbya Guaraní community Puente Quemado 2, which is confronting the Arauco forestry company, the largest landowner in Misiones with 230,000 hectares.

Arauco forestry company in Mbya Guaraní territory

The Puente Quemado 2 community has inhabited 657 hectares for generations, where 46 people live, from children to the elderly. It has had the territorial survey of the National Law 26.160 since 2014, but no state level (municipal, provincial or national) complies with the legislation to recognise the indigenous territory, much less the Judiciary, the main body responsible for enforcing the laws. The multinational company Arauco has advanced on 331 hectares and local businessmen, among them Roberto Ruff, on another 300 hectares.

When you enter the community, you are greeted by the school, the red earth courtyard, some leafy trees and, twenty metres away, the houses, built with wood, sheet metal and black plastic, begin.

Santiago Ramos, 36 years old, is the mburuvicha (cacique) of the community. He greets them with the traditional greeting: he raises his hands slightly, shows his palms and says “aguyjevéte” (a word of welcome with a very spiritual meaning, it is a sacred greeting that represents respect for the other). He invites them to sit in the shade of a tree and asks them to wait for other members of the community to arrive. Two hours after, when three other Mbya are already present (and several others have stopped by to say hello), the formal interview begins. He reviews the state of affairs: bilingual-intercultural education is not provided, they have no water or electricity, they cannot make use of natural resources, they suffer from agro-toxins from forestry companies and, above all, they cannot use the territory that belongs to them. In short, almost none of the rights of the National Constitution are fulfilled. But the Argentinean flag, raised by the teacher when she arrived, is still flying.

“Electricity and water are basic, even if it’s only for the school. It is for the children, to continue studying and also to be able to help the grandparents. It’s a dream we have,” explains the cacique. And he also points out the obstacles to this: the Arauco company demands an agreement (whereby the community cedes the land) and, after that, promises to build a water well and provide electricity. The provincial government (now in charge of Oscar Herrera Ahuad, but always controlled by Carlos Rovira) looks the other way. The Directorate of Guaraní Affairs, the Ministry of Ecology and the Misiones Water Institute look the other way.

He warns that on the issue of housing “there is not so much preoccupation”. He is surprised by the response. And he elaborates: “We know that we do not have a roof over our heads as many people from outside want, we know that we live precariously, but at the same time we live well, let’s say, we do not suffer from any illness and, well, there have been no strong storms, we have our spirituality”.

“We have requested water from the Chamber of Deputies and from the government. But they say they will do that when the land is demarcated so that Arauco can continue planting pine trees,” she complains. Tierra Viva asks her how much land the company wants. Ramos explains: “They want all the land. They say it’s theirs. With the grandfather (the previous cacique) they had offered us only five hectares. Now they have offered us twenty metres beyond the houses. If that’s all we have, we’re going to die.

Photo: Emipa

Photo: Emipa

The fire that restarted the struggle

In the summer of 2022, the Garuhapé area was one of the localities affected by the fires. The Mbya community was literally surrounded by fire. Two of their houses burned down and the elders (grandfathers and grandmothers) had to take refuge in a nearby stream. They remember days of suffocating smoke, flames more than 30 metres high and the fear of loss of life.

They were already familiar with the actions of the monoculture tree plantations, but the fires were the breaking point. In an assembly, they decided that they were no longer going to allow companies to enter, let alone let them plant again.

You can see the thousands of burnt logs standing upright. There are more than 300 hectares. Arauco insists on entering, cutting down what was burnt and returning with new pine trees.

The Mbya rely on ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous Peoples, a human rights treaty that has supra-legal status in Argentina, over and above local laws.

“We did not know what to do in the face of so much fire. Some grandparents grabbed their bags and wanted to leave, but there was nowhere to go. It was all very sad. What little bush we had was burnt. And we lost our medicines. We suffered a lot. Some of us walked around with little buckets… as if we could do anything in the face of so many flames,” says the cacique.

He also recalls that one of the children was almost trapped by the fire, that the firemen were slow to arrive and, above all, that they witnessed how quickly the flames grew and advanced over every metre of the community. Pine trees, a foreign species, spread the fire much more than native trees. The flames devastated hundreds of hectares.

“It was days without sleep. With fear. With a lot of smoke that didn’t let us breathe. We only calmed down after twenty days, because it rained and put everything out. But then came the flood. And now the water is rising to places where it didn’t reach before,” he says.

The peasant and indigenous communities said it before anyone else. When the native forest is destroyed, the soil becomes impermeable, the water can no longer penetrate and, with the rain, flooding occurs.

“The company is responsible. Before the pine trees, there were no poisons, no fire and no floods. All this suffering is because of the pine trees. That’s why we decided, after the fire, that we don’t want any more pine trees, we don’t want any more suffering”, says the mburuvicha and adds: “It made us think that we have to fight for our territorial rights, that the company should not enter any more, because the monoculture of pine trees is a tragedy and we are going to fight to recover the forest”.

Photo: Emipa

Arauco forestry company

Arauco is a multinational forestry company that operates in thirty countries. In Misiones it controls more than 230,000 hectares, ten per cent of the province. No other company or individual in Argentina concentrates so much land in a single province. And it has accumulated complaints from peasants and indigenous peoples for land usurpation, contamination and violation of rights. “The community existed long before the company did. But one day they came and took over everything. And we didn’t have the capacity to confront them,” says cacique Ramos.

It is already noon, time for lunch. They reach for a stew of rice and chicken that the women have cooked in large pots over a wood fire. We all eat under the tree. The recorder is turned off and the conversation turns to football, the visit the cacique made to the city of Buenos Aires (he was overwhelmed by the noise and so many people) and the heat that is beginning to be felt.

During the after-dinner conversation, the interview is resumed. Santiago Ramos summarises: “We are in our territory, and they don’t want to respect us, they put pressure on us and threaten us to let us plant them, but that’s not going to happen. We have rights and they have to respect us.

He says that Arauco offered them “a little piece” of land to plant maize and manioc.

-How much land did he offer them?

-Two hectares for the whole community.

-And how much would they keep?

-Almost all of it.

-The company says they say they want to have a good relationship with you.

-The only good relationship the company has is with those who don’t complain. Because the company does what it wants everywhere. It gets along well with the mburuvicha (chiefs) who don’t complain. That is the “good relationship” that the company wants.

Cacique Santiago Ramo. Photo: Emipa

Cacique Santiago Ramo. Photo: Emipa

Mbya territory and future

The Mbya Guaraní show on the table the map of the territorial survey established by Law 26,160. It is 657 hectares. And they make it clear that it is very simple: “We live like this, in the bush, because we belong to nature. It is our right to walk in the bush and to continue to maintain our customs and education. The ‘jurua’ (whites) have to understand and respect this. The company and the government have to understand and respect this.

He clarifies that they are not against the provincial or national government. They just want the territory surveyed. He laughs when he recalls that a provincial official once called them “invaders” of their own territory. And he smiled even more when Arauco told them that the hectares without pine trees were “unproductive”.

“They don’t understand how important the forest is, all the food and medicine it provides. The forest is life. And if it weren’t for the indigenous peoples, all the native forest would be exterminated by now,” he says.

The seats scurry away in search of shade. Although they are always present, the rest of the Mbya do not speak. They nod, smile and say a few words in Guaraní to the cacique.

“Our dream is to obtain the title of communal property so that we can live in peace, so that no one disturbs us, so that we can work freely, without anyone threatening us. What we are sure of is that we are not going to stop fighting, we are going to remove it and we are going to plant our food,” he warns.

He clarifies that this season is ideal for cassava, maize and sweet potato. And he affirms that they are ready to cultivate, even cutting down the burnt pine trees.

The cacique says a few words in Guaraní to the round of ten people. He looks at the other Mbya and they respond with a gesture of approval. With a smile, he extends his hand in greeting, closes the interview and invites them to visit the territory and the stream (about 200 metres away) that was a refuge from the fire. The children play football with a slightly deflated ball. Meanwhile, the Argentinean flag, very neatly arranged, keeps waving in Mbya Guaraní territory.